What Was The First Makeup Made What Was The Third Makeup Made

This section includes products such as rouges and lipsticks. The text below provides some historical context and shows how we can use these products to explore aspects of American history, for example, the links betwixt changes in American feminine identity and the American beauty manufacture. To skip the text and get direct to the objects, CLICK HERE

|

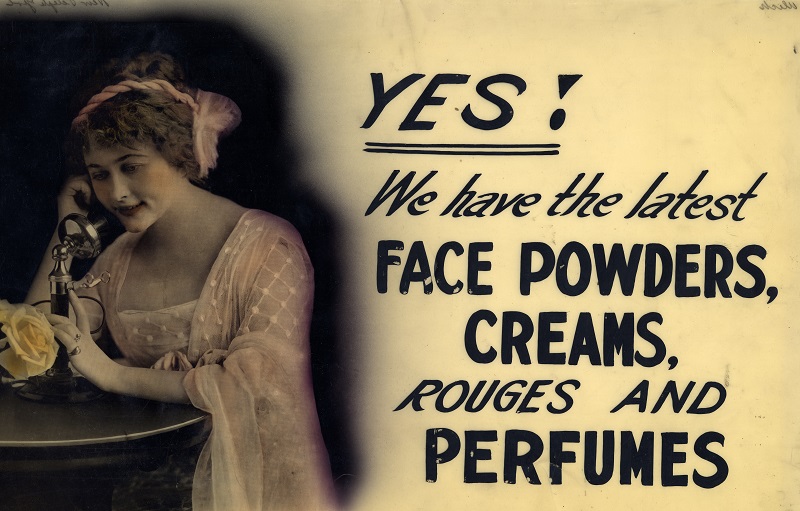

| A shop window advertising sign depicting a stake-complected, red-lipped beauty idealized at the get-go of the 20th century. Warshaw Collection of Business Americana, Archives Heart, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution |

In eighteenth century America, both men and women of the upper classes wore brand-upwards. Simply, shortly after the American Revolution the use of visible "paint" cosmetics (colored corrective for lips, skin, optics, and nails) by either gender gradually became socially unacceptable. For most of the nineteenth century few paint cosmetics were manufactured in America. Instead, women relied on recipes that circulated amidst friends, family unit, and women's magazines; using these recipes, they discreetly prepared lotions, powders, and peel washes to lighten their complexions and diminish the advent of blemishes or freckles. Druggists sold ingredients for these recipes, also as the occasional set up-made preparation. Painting one'southward face was considered vulgar and was associated with prostitution, and then whatever product used needed to appear "natural." Some women secretly stained their lips and cheeks with pigments from petals or berries, or used ashes to darken eyebrows and eyelashes. Woman worked to attain the era'due south ideal feminine identity; a "natural" and demure woman with a pale-complexion, rosy lips and cheeks, and brilliant eyes.

In the 1880s, entrepreneurs began to produce their own lines of corrective products that promised to provide a "natural" look for their customers. Some of these new companies were small, woman-owned businesses that typically used an amanuensis system for distribution as pioneered by the California Perfume Company, later rebranded equally Avon. This business organisation model allowed many women to make money independently. Also, more women were earning wages and buying cosmetics, thereby enlarging the market further. Women could make a living in the burgeoning cosmetics merchandise equally business owners, agents, or factory workers. Most of these entrepreneurs came from fairly apprehensive origins, and some managed to transform their local operations into successful businesses with a wide distribution of their products. Florence Nightingale Graham, for instance, was the daughter of tenant farmers, and worked many low-paying jobs before opening a beauty shop for elite clients and reinventing herself equally Elizabeth Arden. African American women also found success through this model, but faced extra obstacles. Many white shop owners refused to consider stocking African American beauty products until successful businesses similar that of Madam C. J. Walker created enough of a demand through other distribution channels.

Past the 1920s, it was stylish for women, especially in cities, to habiliment more than conspicuous brand-upwards. This shift reflected the growing influence of Hollywood and its glamourous new picture stars, also every bit the fashion of theater stars and flappers. "Painted" women could now besides identify as respectable women, even as they wore dramatic mascara, eyeliner, dusky eyeshadow, and lipstick like the stars of the screen. The growing ethnic diversity of the U.s. also influenced how cosmetics companies marketed their products. "Exotic" or "alluring" ethnic stereotypes became inspirations for make-upwards fashions that ostensibly reflected the American melting pot. White women could experiment with a trendy, exotic identity – and then wash it off. African American identity, however, was explicitly excluded from this ethnic mingling. In the late 1920s and 1930s, it became fashionable for white women to sport the appearance of a "healthy" tan. Previously, a tan had been equated with working-class women who performed outdoor labor; at present a tan identified a adult female every bit modern and salubrious, participating in outdoor recreations and leisure. Brand-up colors were marketed in various "suntanned" shades, giving women the pick to remove the "tan" whenever they wished to repossess a fair complexion.

At this time, the cosmetics concern experienced a major shift. Small cosmetics companies, many of which were owned by women, were replaced by larger corporations. Business concern models had changed: in order to remain competitive and achieve wide distribution, a business concern had to engage in wholesale bargaining with male-owned concatenation drug and department stores. Because women were usually excluded from these distribution channels, most female-endemic businesses could not compete. By 1930, a pocket-sized handful of companies controlled xl% of the cosmetics industry. These companies now released thousands of mill-produced, like products under various brand names.

|

| 1930: The J.R. Watkins Company owned the Mary King Cosmetics line. Here, agents sell Watkins products and Mary King cosmetics. Scurlock Studio Records, Archives Eye, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution |

Spending on cosmetics increased dramatically when millions of women entered the workforce during the 2nd World War, gaining greater independence and purchasing ability. Younger women embraced an overtly flirtatious persona, signaled through the conspicuous use of bold rouge, powder, lipstick, and nail smoothen. Many working women wore shorter, more "manly" hair styles, and brand-up was used to reassert femininity. When nylon stockings became unavailable because of state of war-time article shortages, women turned to leg brand-upwardly—pigment-on hosiery maintained the illusion of nylon-clad legs. Cosmetics advertisements and war machine recruiting campaigns during the war emphasized women's dual responsibilities: support the state of war effort and maintain one'southward feminine identity through the utilize of make-upward. Government-produced posters encouraging women to bring together the war effort depicted female nurses and factory workers in bright red lipstick and dark mascara. Makeup, particularly lipstick, had become such an essential component of American femininity, that the federal government quickly rescinded its wartime materials-rationing restrictions on cosmetics manufacturers in gild to encourage apply of make-up. Equally Kathy Peiss writes in "Hope in a Jar," the utilise of brand-up had go "an exclamation of American national identity."

After the state of war, lxxx-90% of American women wore lipstick, and companies like Avon and Revlon capitalized on this now-ingrained fashion. By the 1950s and 1960s, teenage girls were unremarkably wearing make-upwards and cosmetic companies devised separate marketing campaigns to target the younger age groups.

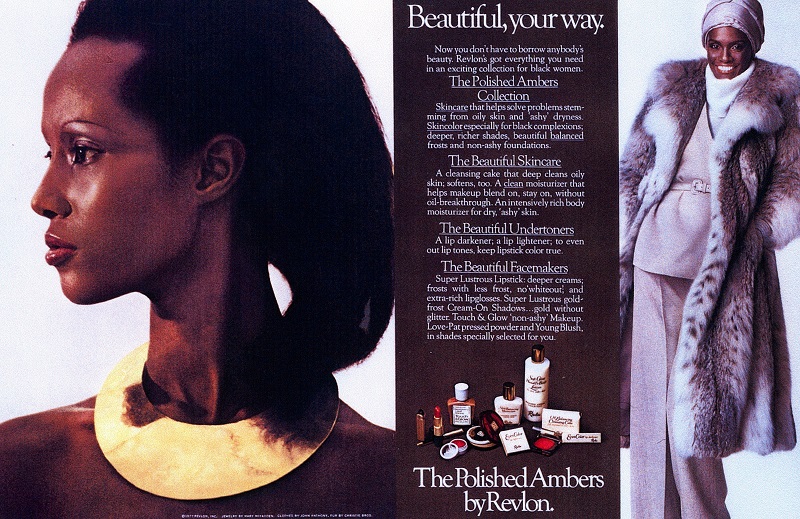

In the late 1960s, using makeup became politicized. Counter-cultural movements celebrated ideals of natural beauty, including a rejection of make-up altogether. Cosmetics companies returned to advertisements that claimed that their products provided a "natural" look. These ideals still relied on racial whiteness as the footing of feminine beauty, but under continued pressure level from women of colour, major cosmetics firms began to cater to the African American marketplace, non only past producing products geared toward black women (often nether separate brands), merely as well past hiring black women equally sales agents. However, the so-called "ethnic" segment of the cosmetic market remained small, making upwards only two.iii% of total sales in 1977.

|

| 1977 Revlon advert campaign for the "Polished Ambers collection...an exciting collection for blackness women." Revlon Advert Drove, Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution |

Bibliography ~ see the Bibliography Section for a full list of the references used in the making if this Object Group. Yet, the Make-up section relied on the following references:

Gill, Tiffany M. Beauty Store Politics: African American Women's Activism in the Dazzler Industry. Urbana; Chicago: University of Illinois Printing, 2010.

Jones, Geoffrey. Beauty Imagined: A History of the Global Beauty Manufacture. Oxford; New York: Oxford Academy Printing, 2010.

Jones, Geoffrey. "Blonde and Blue-eyed? Globalizing Beauty, c.1945–c.19801." The Economical History Review 61, no. i (February 1, 2008): 125–54. doi:x.1111/j.1468-0289.2007.00388.x.

Morris, Edwin T. Fragrance: The Story of Perfume from Cleopatra to Chanel. New York: Scribner, 1984.

Peiss, Kathy Lee. Hope in a Jar: The Making of America's Beauty Culture. New York: Metropolitan Books, 1998.

Scranton, Philip. Dazzler and Business: Commerce, Gender, and Civilisation in Modern America. New York: Routledge, 2001.

Source: https://www.si.edu/spotlight/health-hygiene-and-beauty/make-up

Posted by: perrylitsee.blogspot.com

0 Response to "What Was The First Makeup Made What Was The Third Makeup Made"

Post a Comment